How Disability Stories Bridge The Gap

It happens to me regularly. I’ll be in a grocery store, a restaurant, maybe on the sidewalk in front of my apartment building, heading for the garage. A group of kids spots me and freezes—startled by my hand deformities, the unusual crutches I use to get around and my labored gait. They stare, wide-eyed, mouths agape.

It doesn’t really bother me (okay, it bothers me a little) because if I were in their shoes and had never seen or read about someone who looks like I do, that would likely be my response too. Theirs is a very human reaction to a new experience—and one of the reasons why including disabled characters in children’s literature is so vitally important.

I have a strategy for dealing with these situations when they come up: I introduce myself to the kids and ask if they have questions, often leading with, “Are you wondering what happened to my hands?”

Nearly 100% of the time, their reaction is relief. They were confronted with this weird, unusual, possibly even a bit frightening sight and someone is offering to explain the situation to them. Smiles break out on their faces and they say, often in unison, “Yes!”

What’s even more telling is that, after I fill the kids in on how I was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at 13 and how that illness affected my joints over the years, they inevitably start telling me stories of their own—how one had her tonsils out and another broke his arm or others have a grandparent who has arthritis or a neighborhood friend who uses a wheelchair.

Stories which provide information and representation really matter in bridging the gap between discomfort and familiarity, between fear of the unknown and true empathy.

The robust and honorable push for diversity in media has been somewhat slow to include disability, with some of the diversity programs in the film and television industries still not recognizing disability as a qualifying category for entrants. The world of children’s literature, however, has always been somewhat ahead of the curve.

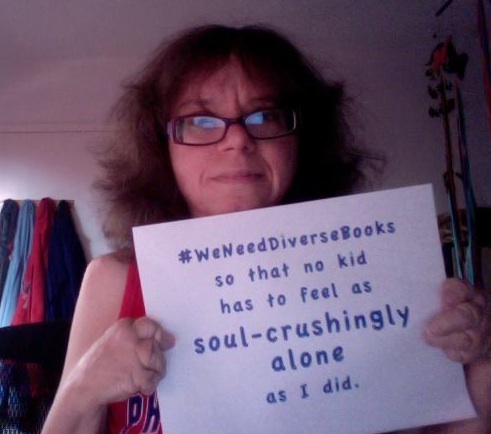

We Need Diverse Books, started in 2014, not only included disability from its outset but does so in an incredibly comprehensive way, with their definition extending to chronic illnesses and any physical and mental conditions which result in societal barriers. (You can check out the full definition on the About WNDB page on the organization’s website.)

The world of children’s literature also brings us the Disability In Kidlit website, a source for middle grade and young adult books featuring characters with disabilities, again employing a wide, inclusive net for their parameters.

The site requires that all book reviewers share the same disability as the character in the books they review—going the extra mile to ensure informed opinions on the accuracy of the portrayals.

Interestingly, it was one of the site’s co-founders, sci/fi writer Corine Duyvis, who coined the now well-known #ownvoices hashtag. She suggested the hashtag in a September 2015 tweet as a way to easily identify middle grade and young adult books written by authors who belong to the same marginalized communities as the main characters in their books. A movement was born, with the hashtag now being used by agents, editors, and booksellers. (Check out Duyvis’ funny and far-reaching suggested guidelines for use of the hashtag on her #ownvoices FAQs page.)

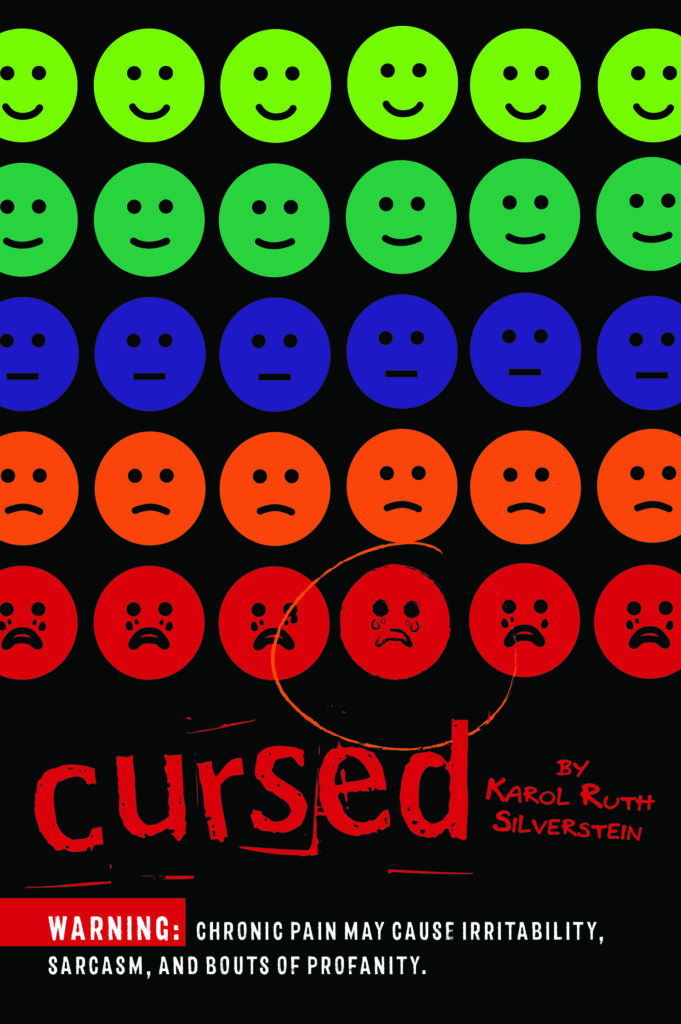

My young adult novel Cursed, coming out June 25 from Charlesbridge Teen, is about a young teen newly diagnosed with a painful chronic illness and was drawn from my own experience of the same diagnosis.

While I don’t consider my main character Ricky disabled specifically, her chronic illness and the societal barriers and stereotyping she’s subjected to, fall well within the broad definition of disability used by We Need Diverse Books.

One of the things I really wanted to illuminate was what it’s like to live with near-constant chronic pain—and not just the physical aspects of that life, but the mental and emotional toll it takes. It’s a more complicated and all-encompassing situation than many people realize. (Able-bodied folks can take a scroll through the #ThingsDisabledPeopleKnow hashtag on Twitter to get a sense of how much they might not know about the actual nuts and bolts of living with a disability.)

I felt soul-crushingly alone as a teen. The value of having a book like Cursed available to me back then would likely have been immeasurable.

Additionally, while a good number of books feature supporting characters—a sibling, a school friend—who has autism, uses a wheelchair or deals with some other physical challenge, it’s significant that my chronically ill kid is front and center. Ricky also tells her story in first person-present tense, allowing readers to essentially live in her skin for the duration of the novel.

Although I’m writing here mostly about the benefits of exposing non-disabled readers to accurate, multidimensional disabled characters, it’s important to note that for kids who have disabilities and health challenges themselves, seeing themselves represented in media is incredibly important.

I felt soul-crushingly alone as a teen. The value of having a book like Cursed available to me back then would likely have been immeasurable.

During the submission process, my agent Jen Linnan asked me for permission to specifically pitch the story as #ownvoices. I’m fairly open about my disability online, but she didn’t want to make any assumptions. I gave her my blessing, and we both feel it helped us find the book a great home.

My editor, Monica Perez, told me one of the things that drew her to Cursed was that chronic illness and physical disabilities weren’t tackled much in YA.

Neurodiversity, a wide umbrella term covering everything from dyslexia and ADHD to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, has been experiencing a welcomed boom of representation, but the physical disability experience is still less common. Stories that feature disability or medical conditions written by authors who have disabilities or medical conditions themselves make up an even shorter list.

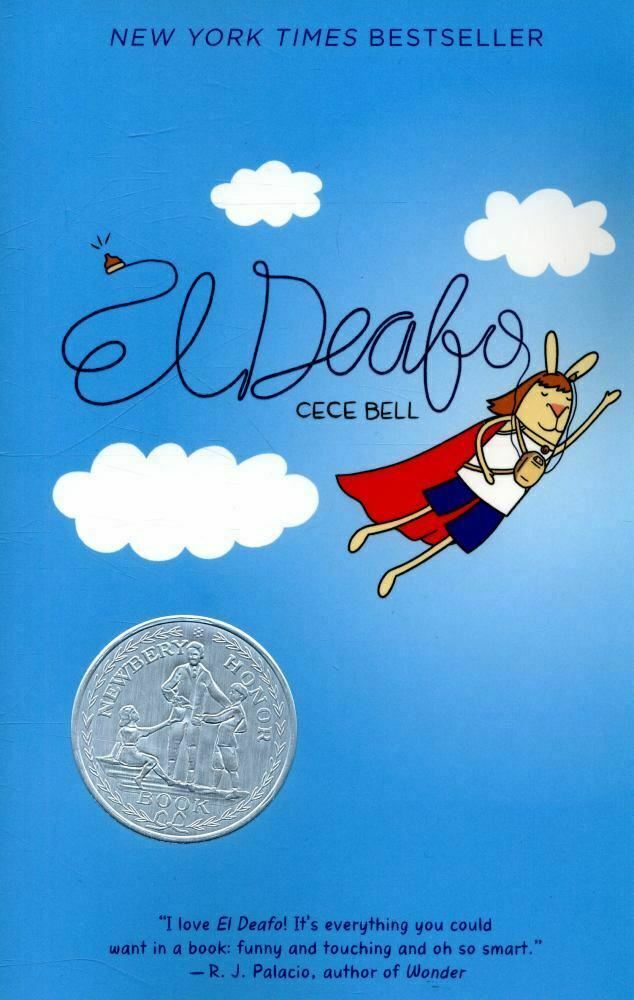

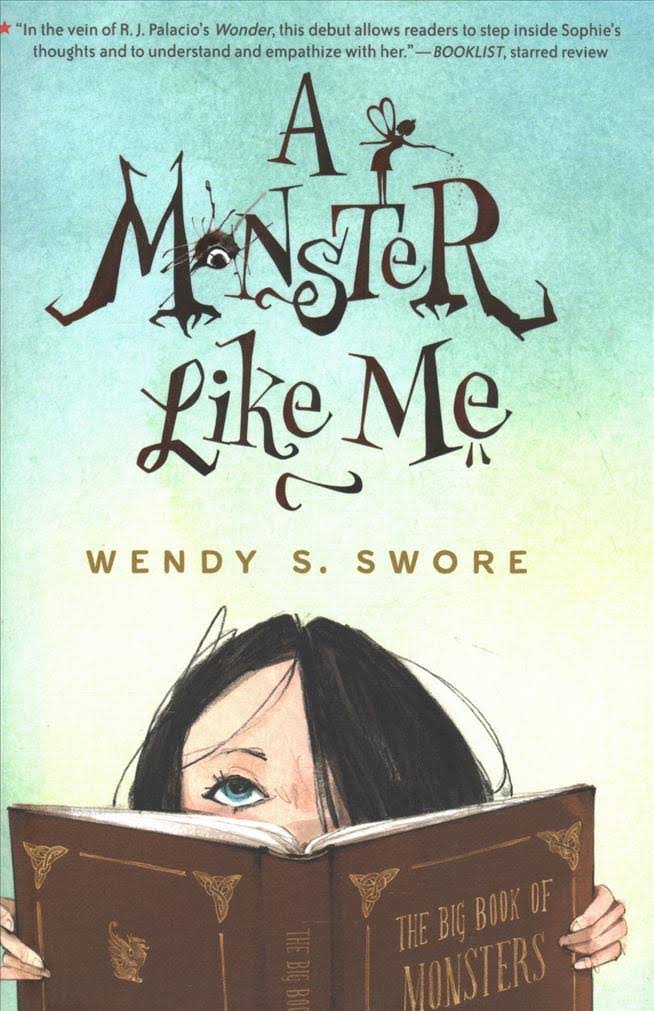

One can look at the marvelous middle-grade graphic novel El Deafo by Cece Bell to witness the full potential of #ownvoices disability-themed books. The newly released middle grade novel A Monster Like Me by debut author Wendy Swore is another great example of an #ownvoices book where the main character has a fairly common medical condition (but one that’s unfamiliar to most kids). The story is about grade-schooler Sophie, who’s obsessed with monsters and believes she is a monster due to the hemangioma covers much of the side of her face. In an early scene at a grocery store, a grownup points Sophie out to her kids and jokes that Sophie doesn’t need a costume for Halloween. Swore, who also had a hemangioma as a kid, tells readers in an author’s note that the rude woman’s dialog was a direct quote from an insult hurled at her by an adult when she was a child.

Ultimately, the best stories featuring characters with disabilities and medical conditions—really, the best stories period—garner empathy rather than sympathy.

In a future with far more genuine depictions of disabilities and physical differences appearing in not only children’s books but in film, TV, advertising—anywhere disabled people are, which is everywhere—I predict that my public encounters with startled children will decrease significantly.

Until then, I remain ready to disarm kids with my stories about why I look and move differently—and I look forward to hearing their stories, too.

chat 4 Comments

Great article. Relevant and important. The links are very helpful also. Thank you!

What a beautiful article. I can’t wait to read CURSED!

Honest, insightful, and highly informative article. Can’t wait to read CURSED!!

Enlightening at so many levels! Thank you for this article, and for CURSED.